Bottle production was the mainstay of the American glass industry from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many are purely utilitarian, yet a great number reveal a simple beauty. The paper will consider first the small pocket bottles that survive in large numbers. Blown in dip molds in jewel-like colors, they remain among the most graceful of early American glass products. The paper will further explore their early manufacture in America, the individual glasshouses that made them, their relationship to tablewares produced, and the cross-fertilization of the English and German traditions. An important facet of bottle production in American glasshouses toward the middle of the nineteenth century was the production of what were known in the period as “figured flasks.” The paper will also discuss these often engaging liquor bottles that were blown in two-part molds with designs relating to popular taste and events.

Bouteilles et flacons en verre américain

La fabrication des bouteilles représente l’activité principale des verreries américaines pendant le XVIIIe et le début du XIXe siècles. Objets utilitaires, certaines se révèlent d’une grande beauté.

Il sera d’abord question des petits flacons de poche, nombreux à être parvenus jusqu’à nous. Soufflés dans des moules fermés, à l’aide de verres de jolies teintes, ils sont des témoignages particulièrement heureux des premières réalisations de verre américaines. Seront évoqués les premières verreries, leurs lieux de production et leurs liens avec les services de table, sachant que cette industrie profite de l’enrichissement mutuel des traditions anglaises et germaniques.

Une partie importante de la production américaine du milieu du XIXe siècle est constituée par les bouteilles de liqueur dites « à sujet » dont les motifs reflètent le goût populaire et les événements contemporains. C’est leur fabrication, en verre moulé dans des moules ouvrants en deux parties, qui sera en dernier lieu considérée.

This paper has been published in:

Flacons, fioles et fiasques. De l’Antiquité à nos jours. Les Cahiers de Verre & Histoire no 3, Actes du troisième colloque international de l’Association Verre & Histoire, Rouen-Vallée de la Bresle, 4-6 avril 2013, Carré A.-L. et Lagabrielle S. (dir.), Paris : Éd. Verre & Histoire, mai 2019, p. 153-164.

Bottles and flasks form the primary output of American glassmakers throughout the early history of the glass industry in the United States during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While bottles intended for alcoholic beverages comprise the greater part of glass vessels produced, smaller bottles for more specialized uses were also in demand in the American colonies. Glass smelling bottles, for example, were advertised frequently in American newspapers between 1760 and 1790. One Connecticut merchant promoted: “Smelling Bottles of various shapes, so absolutely necessary for little Misses in the approaching hot season.”1 The straight or twisted rib-molded smelling bottle was a standard type blown in England and America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in blue, green, amethyst, colorless, and opaque white glass. “Twisted” smelling bottles [Figure 1], some described as of opaque white glass, were among the products introduced in 1769 by English émigré glassblowers working in William Stiegel’s Manheim, Pennsylvania, factory, one of the first successful glassmaking enterprises in America.2 It is virtually impossible, however, to distinguish American ones from similar examples produced in Britain.

Other examples demonstrate the characteristic melding of German and English traditions. Applied and pincered decoration was a typically Germanic feature, which could be found on smelling bottles dating as late as 1827, when in the records of the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company, pungents (or smelling bottles) were described as having three or four “pinches” or “pinchons.”3 As the name implies, smelling bottles contained smelling salts, although some may have also held fragrant scents.

Snuff Bottles

Snuff bottles were among the items advertised by most colonial glasshouses, and they continued to be manufactured by bottle factories throughout the nineteenth century. In 1750 the Female Spectator cautioned: “The snuff box and smelling bottle are pretty trinkets in a ladies pocket and are frequently necessary to supply a pause in conversation, and on some other occasions; but whatever virtues they are possessed of they are lost by too constant and familiar use, and nothing can be more pernicious to the brain, or render one more ridiculous in company than to have either of them perpetually in one’s hand.”4 Enterprising merchants had printed labels extolling the virtues of their products. Charles and George Sweetser, for example, did a thriving business selling snuff and cigars at their establishment in Boston between 1858 and 1870, and a bottle with a fragmentary original label for “Scotch Snuff,” is in the collections of the Winterthur Museum [Figure 2].5

Medicinal Bottles

Medicinal bottles were also part of the glassmaker’s oeuvre. Robert Turlington’s “Balsam of Life,” for which he obtained a patent in 1744, with its over twenty-seven ingredients, was a costly but popular antidote on both sides of the Atlantic for nearly a century. One Philadelphia merchant had 2 ½ dozen Turlington’s Balsam Bottles in stock at the time of his death in 1772.6 Turlington tried a number of different styles of bottles until motivated by unscrupulous people who bought empty bottles and “basely and wickedly put therein a vile of spurious Counterfeit” formula, he developed an angular style in 1754 that became the hallmark of his medicine.7 His actions notwithstanding, the bottle was pirated even into the twentieth century and is documented as having been made in at least three glasshouses in the United States in South Boston, Massachusetts, Dyottville, Pennsylvania, and Mount Vernon, New York.8

Bottles For Spirits

Those examples aside, American glassmakers’ largest output was the making and selling of vessels in which to contain alcoholic spirits. After window glass, bottles and other containers were the chief glass products made in America from the eighteenth through the early nineteenth century. Glass bottles were ubiquitous in American households (virtually every household, no matter how modest, had at least one glass bottle), but virtually all made in Europe. Literally millions of English bottles were exported to America beginning in the mid seventeenth century up through the mid-nineteenth century.

Containers for rum, gin, whiskey, porter, beer, and cider were in especially high demand for a society with arguably excessive alcohol consumption.9 Based on surviving examples and archaeological findings, bottles imported during the eighteenth century conformed to the standard shapes and sizes. Some of those were specially ordered. One of the earliest made for an American settler is a globular example, bearing the seal of William De Peyster of Albany, and dated 1726. A later example has a seal for New York City resident Thomas Cornell Pearsall, a “bon vivant, who gave the best dinners & best wines”.10 The bottle bears a rare original label from Murdoch, Masterton & Co., prominent wine merchants in Madeira, known for their especially fine eponymous product. But even the large number of imported bottles was not enough to meet the demand as emphasized in a Baltimore paper in 1789, whose correspondent wrote that: “No factory is more wanted… than a capital glass manufactory for bottles similar to those of Bristol in Great Britain. Considerable orders for Philadelphia beer and porter are now in the city, some of which cannot be executed for want of proper bottles. While France is discouraging glass-works, for want of wood, the United States should establish theirs for her wood is in many places an encumbrance.”11

Colonial Glass Factories

This unmet demand was but one impetus for Caspar Wistar to embark on building what would become America’s first successful colonial glassworks. In 1717, the twenty-one-year old Wistar immigrated to Philadelphia from Hilspach, Germany, near Heidelberg. Not a glassblower himself, this self-styled entrepreneur founded his glass works in Southern New Jersey in 1738 with a handful of immigrant glassblowers from Germany, and commenced production in 1739. It is interesting to note, especially in light of the aforementioned comment from the Baltimore reporter, that Wistar’s glass furnace consumed 2,400 cords of wood per year (operating only seven months of the year), causing Wistar to also embark on an ambitious reforesting program in order to ensure an adequate supply of fuel.12 His glass was typical of the waldglas production of central Europe. They produced some window glass, but bottles formed their major thrust.

Wistar produced bottles of many shapes and sizes, ranging in capacity from half pint to one gallon. And it was considerable at perhaps over 17,000 per year.13 In spite of their large output, only two bottles survive that can be documented to the factory, let alone any colonial American manufacture. In their overall shape they compare with the Breese bottle of 1765, but they also demonstrate that with their wood-fired furnaces, colonial American glasshouses could not make the thick-walled, dark green glass found in bottles from England’s coal-fired furnaces. They bear a seal with the initials RW, for Caspar’s son Richard, and have other features distinctive to that factory, such as the short cylindrical body and tall tapering neck, thick folded lip (which matches archaeological fragments), and a very low basal kick or push up. They also advertised that they made molded case bottles with flat sides intended to be stored in wooden cases, in 2 and 3-quart sizes, although no documented examples are known today.

A drinking bottle that belies the German heritage of Wistar’s workers is one of two examples of a whimsical typically Germanic dog-shaped vessel that relates closely to the schnapshunde popular in Europe from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Period documentation reveals that the Wistar works also made phials and special chemical and apothecary bottles.14

Pocket bottles represent the type of flask that survives in the largest numbers from the eighteenth-century America glass industry. These small spirit bottles that fit into one’s pocket are of the type of “half pint flat Dram Bottles” sold by merchant Thomas Tisdale, who advertised them as “suitable to carry the comfort of life into the field.”15 The majority of such flasks are amethyst in color. A few are plain, but most are dip-molded. Many have been analyzed and are remarkably homogeneous in composition. Close examination of defects in the molded designs also shows that there was probably only one mold used for each pattern, which in turn suggests that a single manufacturer could have been responsible for the entire group of bottles.16 Given the documentary evidence and their probable date they were likely the product of Henry William Stiegel’s glasshouse operating in Manheim, Pennsylvania from 1769 to 1774. It is not yet known where his molds came from, but they were probably made under his direction.

The concept of decorative pocket bottles, of course, is rooted in Continental traditions, but the consistency and quantity of those made in America is significant. Floral molded patterns, similar to the distinctive daisy within a hexagon pattern or daisy in a diamond pattern [Figure 3], were made in southern Germany and Bohemia in the eighteenth century as well. The inspiration for the pattern may have been cut floral motifs common to case bottles. Interestingly, although many European bottles were blown by the half-post method, none of the American ones in this group were, even though immigrant German workmen probably made them. In form, Continental European flasks are also general flatter and wider than their American counterparts, which are of a fairly uniform size and have a distinctive puffy shape. The Stiegel attribution is furthered by the fact that when nonimportation agreements in response to the Townshend duties of 1767 effectively removed English glass from the market, Stiegel revamped his factory to produce refined glass in the English style, and hired English glassblowers and technicians. Furthermore, they began to produce lead glass from raw materials in 1771. These, thus, are a product of a truly American cross-fertilization of English and German traditions that give them their unique character: essentially Continental forms in refined lead glass, a result of English glass technology.

Only one such flask has a history to the eighteenth century. Molded in the diamond daisy design, the bottle bears the diamond point initials of its original owner Elizabeth Shinn Armstrong of Medford, New Jersey (not far from the Stiegel operation). Elizabeth married John Tours Armstrong in 1764, and the flask descended in her family.17 Although pocket bottles in eighteenth-century records are clearly associated with alcoholic beverages, there is indication of multiple uses. Armstrong’s bottle bears an original though fragmentary paper label for “Camphor” from a Maryland pharmacist. Another has a paper label inscribed: “This bottle belonged to my maternal grandmother Rachel Ferm & contained Lavender water distilled by her.”18 Given the gender of ownership of the two documented bottles, it is tempting to speculate that far more of these delicate bottles were made for such uses than has traditionally been acknowledged.

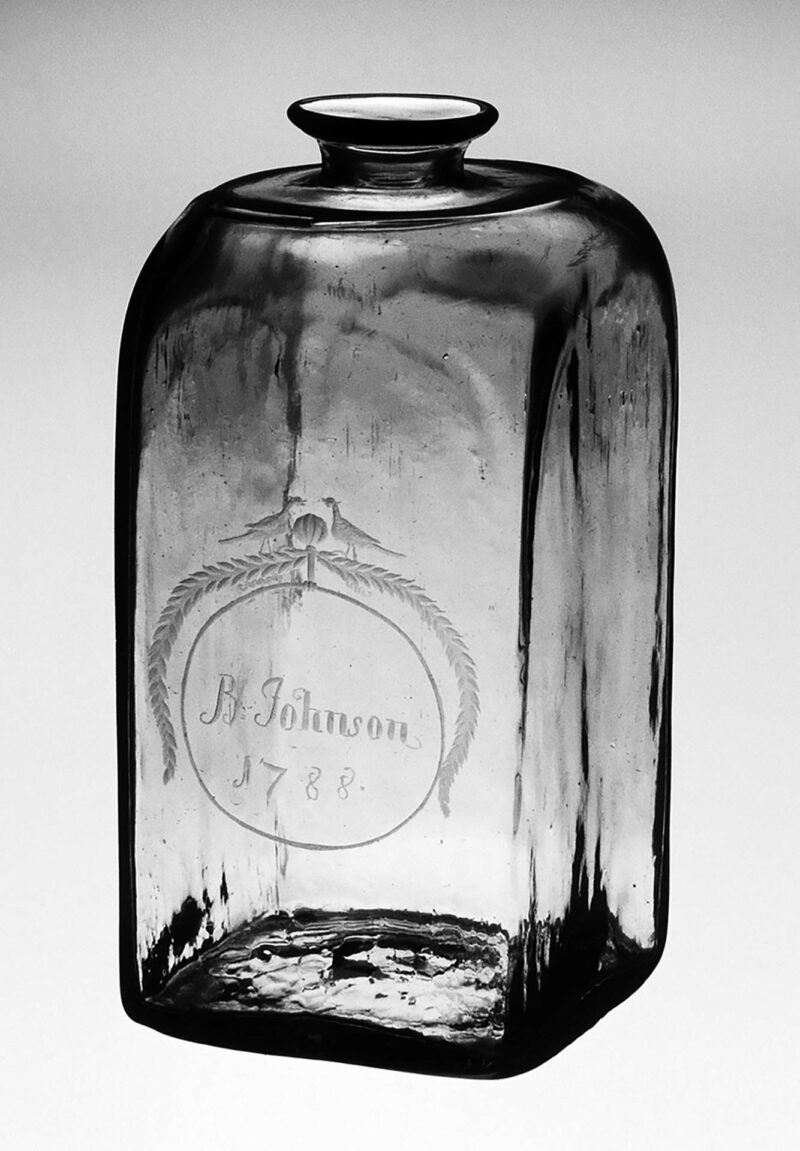

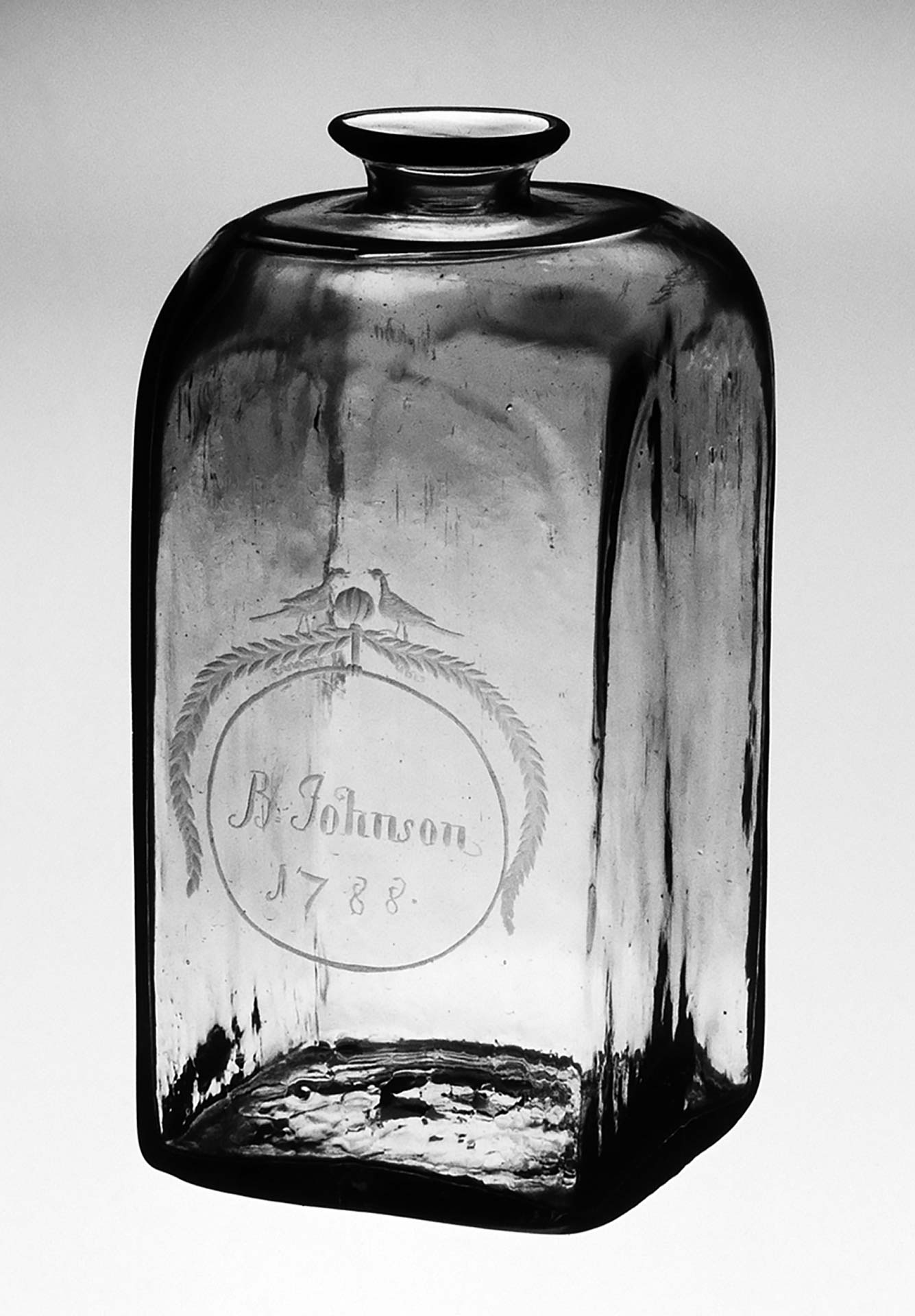

Fragments of the so-called checkered diamond pattern have been excavated from the site of the Maryland glass factory that John Frederick Amelung founded in 1788.19 This pattern is generally known in European production and fragments have been found at Grunenplan, a German glassworks where Amelung worked. The Amelung firm was better known for their engraved glassware, as seen in a square-sided case bottle dated 1788 [Figure 4].

Nineteenth-Century Factories

The use of dip molds persisted among bottle makers in the United States through the first half of the nineteenth century. Certain differentiations in color and shape have been linked with eastern versus western regions. The Midwestern varieties display ribbed or swirled-rib patterns that complement broad flattened shapes typical of the area. Pocket bottles with molded rows of fifteen diamonds were made during the second quarter of the nineteenth century in glasshouses of western Pennsylvania and Ohio [Figure 5]. Others were dipped, swirled, and then dipped again to achieve a rope-like or basket weave pattern. These, too, are typical of the western Pennsylvania or Ohio factories. Blue was an especially unusual—and effective—color.

A group of bulbous bottles have always been associated with Ohio River valley production [Figure 6], although curiously, no documented examples are known. They were made in varying sizes, although they were typically about 8 inches high. Amber was the most common color, but others are known. Dating is confirmed by a remarkable aqua example with swirled ribs that has in its base the impression of an 1846 coin. Like the smaller pocket flasks, these too, although rarely, featured the double-dipped broken swirl design.

England factories, by contrast, were more closely associated with examples with fine swirled ribbing and fashioned by the half-post method, where a second layer of glass falls short of the full length of the first gather or post, generally of olive greens and amber color reflecting the natural unrefined glass [Figure 7].

“Figured Flasks”

“Figured flasks,” as a large group of small-sized decorative liquor bottles were called in the period, represent an extraordinarily important facet of bottle production in the United States during the nineteenth century, and this was a particularly American phenomenon [Figures 8, 9].20 Blown in two-part, full-size molds, the designs on these flasks provide an excellent index to popular taste of the time. American glassmakers did not invent the full-size mold, but they fully exploited its use to produce bottles and flasks, as well as tablewares and some lighting devices, uniform in size, decorated, and made at a lower cost than the more labor-intensive free-blown wares. Made primarily as pocket bottles for spirits, their popularity was owing to enterprising—and highly competitive—makers who developed attractive, topical wares.

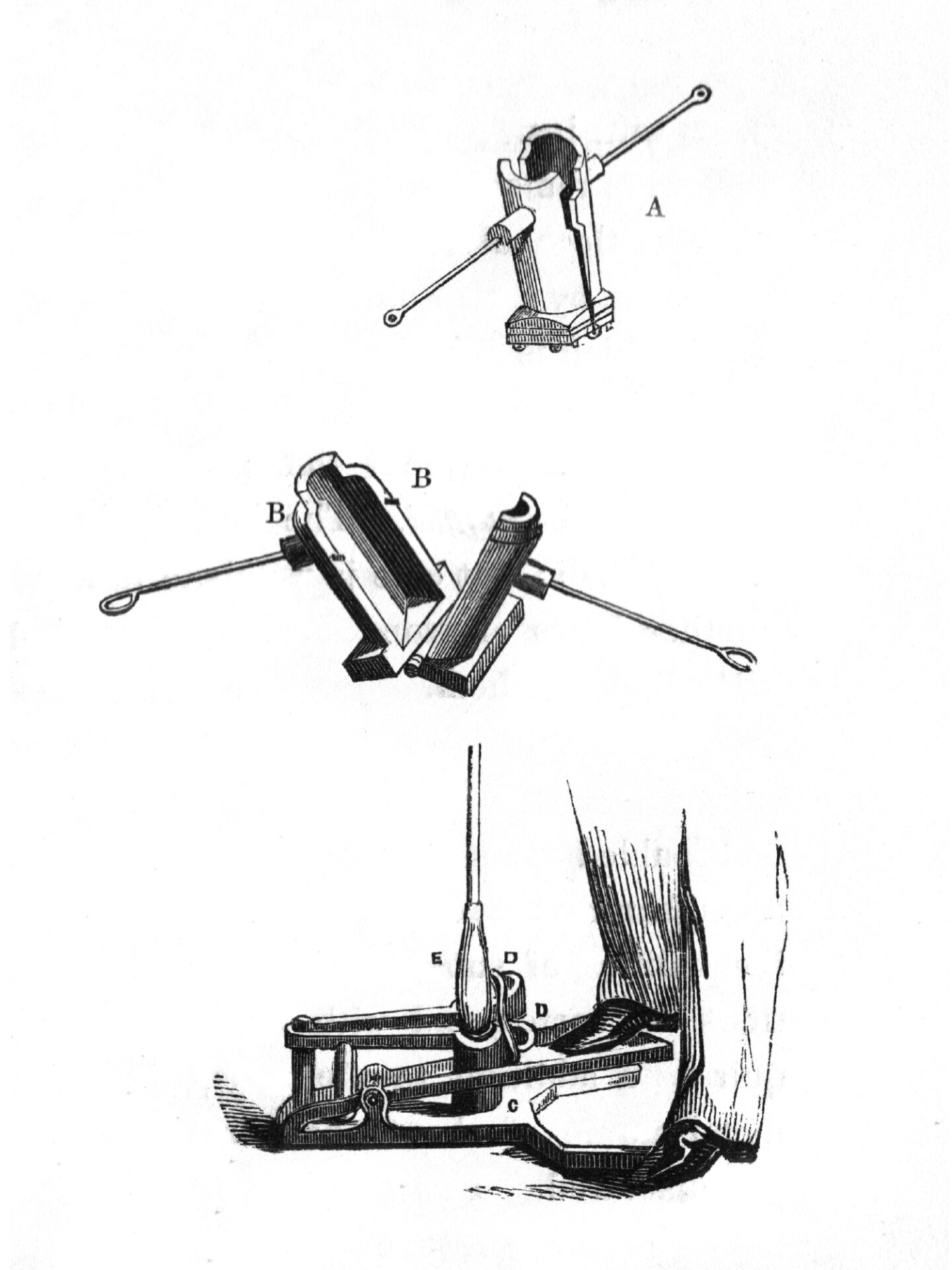

They were made in full-size cast-iron, bronze, or brass molds, usually composed of two vertical sections, one forming the obverse and the other the reverse. The base was usually integral with the side sections, though some molds had separate base plates. At first, molds were opened and closed by a glassblower’s assistant, usually a boy, though by at least 1850, as published in Apsley Pellatt’s Curiosities in Glassmaking, some molds could be opened and closed with a foot treadle [Figure 15].21

The first figured flasks in America may have been made by Thomas Cains of South Boston, who developed the full-size mold by 1815.22 Bakewell of Pittsburgh may also have been producing them early on as did the glass factory operating in Keene, New Hampshire, whose principal Timothy Twitchel could have seen early masonic and sunburst flasks being made when visiting the South Boston works in 1815.23 The first published mention of figured flasks appeared in an 1822 advertisement for “American Eagle, Masonic Pocket, ship, Franklin, and Agricultural bottles,” by Thomas Dyott, a patent medicine manufacturer. A more extensive advertisement by Dyott in the United States Gazette of 3 March 1825, suggests the scale on which these were made, indicating that they had 3,000 dozen pint flasks in the “Washing and Eagle” pattern alone.24 Dyott’s patent-medicine business was so successful that from 1820 to 1839, he operated his own works in Philadelphia, and was one of the most skilled at marketing, developing a wide network of traveling salesmen and distributors.

Figured flasks were made by at least eighty-two different glasshouses, and from New England to Louisville, Kentucky; more than 750 patterns have been identified. The earliest were geometric designs of classical inspiration that reflect broader currents in the arts. The designs embraced many subjects, though patriotic nationalism and contemporary politics were the chief inspirations until 1840. The importance of patriotic symbols is demonstrated by the wide proliferation of eagle flasks made by numerous glass factories [Figure 10]. Designs on flasks are indicators of strong Masonic involvement in American citizenry. Some demonstrated both patriotic and local pride: glasshouses from Baltimore feature the famous Battle Monument and the Washington monument.25 Post-Civil War themes help to date these flasks. Others feature designs relating to westward expansion [Figure 11].

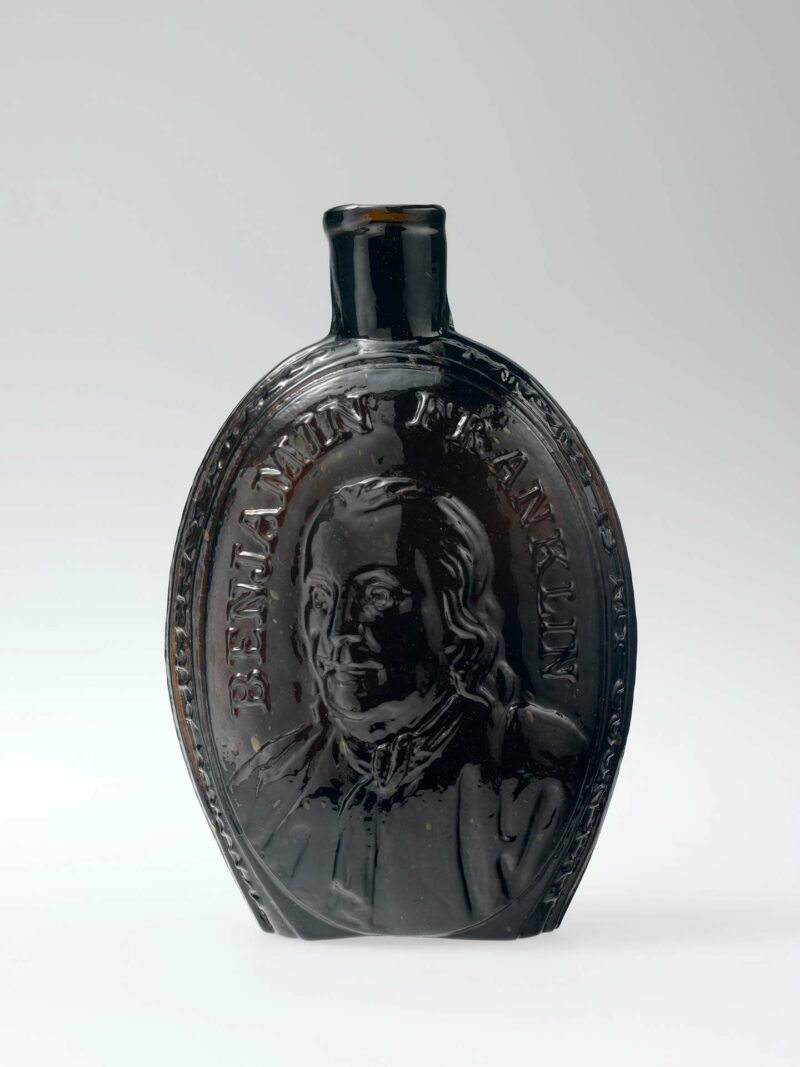

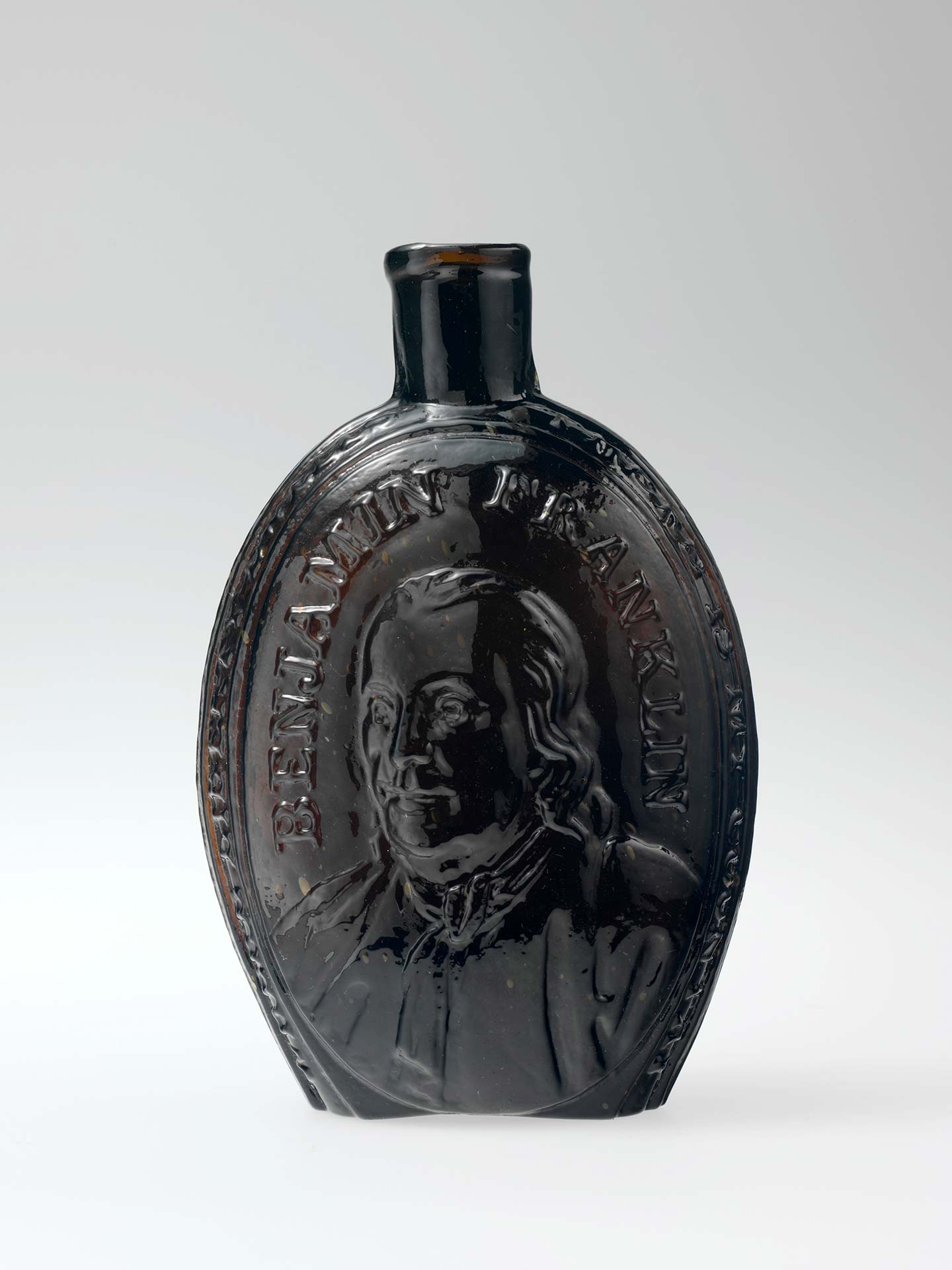

Portrait flasks honored historical heroes and contemporary famous personages. George Washington’s was the face most commonly rendered on glass, but Benjamin Franklin and others were represented as well. The visage of General Lafayette, the French hero of the America Revolution whose triumphant return in 1824-25 spawned a new era of souvenir goods, appears on glass flasks from several different factories. Dyott, self-proclaimed doctor and entrepreneur, and glassmaker, thought fit in at least two versions to immortalize his own likeness on a flask with fellow Philadelphian, Benjamin Franklin [Figure 12].

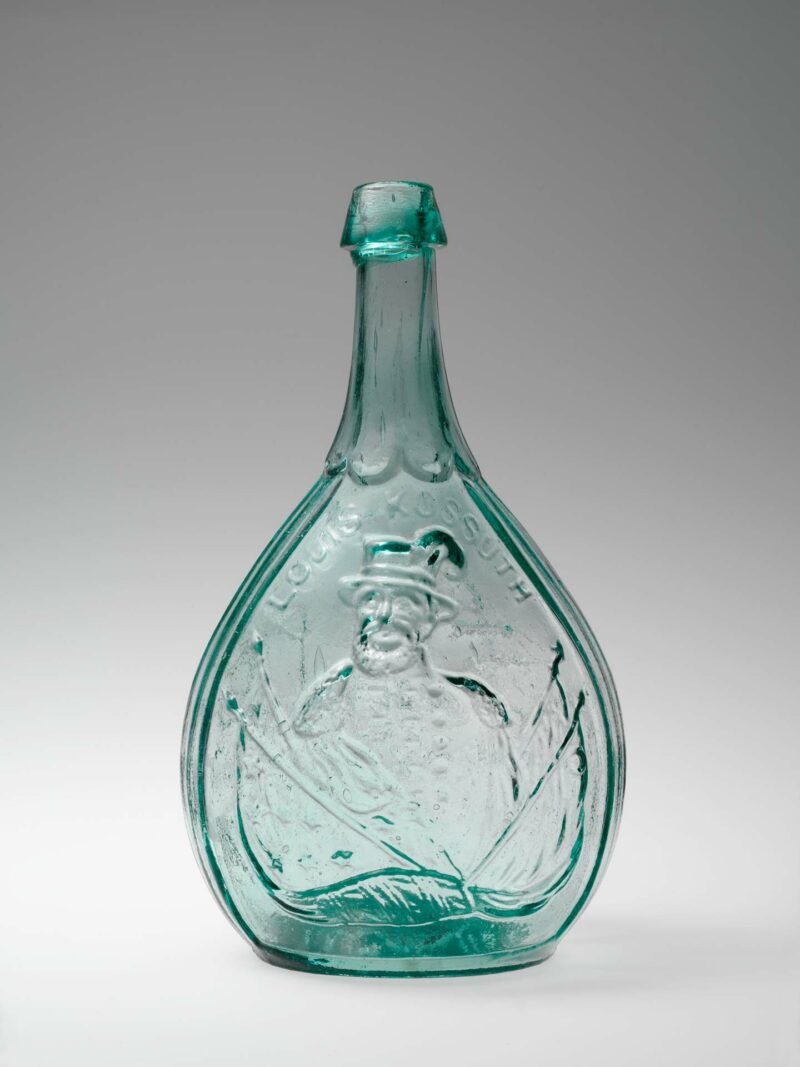

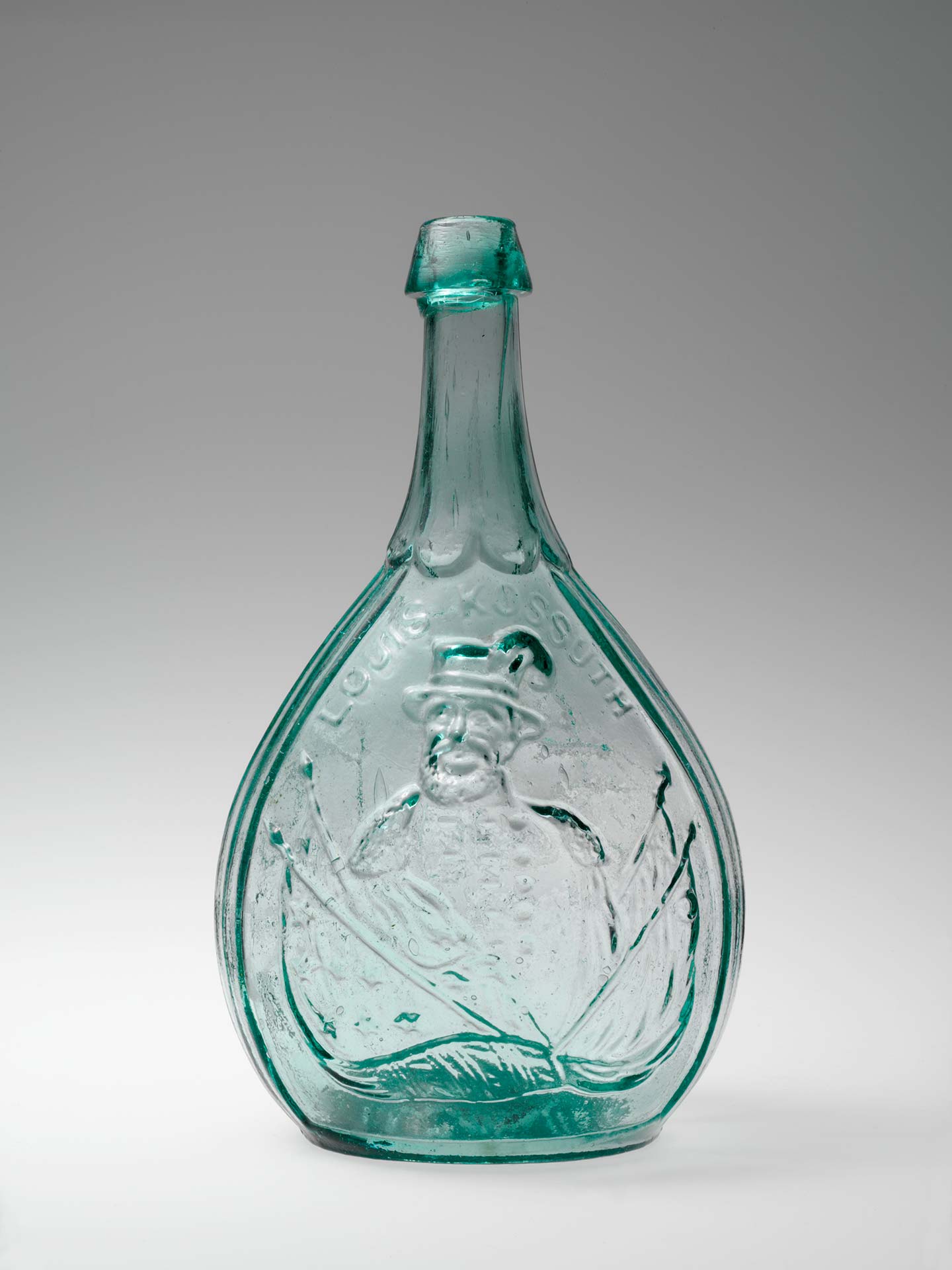

The popularity of European celebrities who took the country by storm in the 1850s provided commercial opportunities for competitive and enterprising glass houses. Flasks appear with both Jenny Lind, dubbed the “Swedish Nightingale,” and Louis Kossuth, the Hungarian revolutionary who came to the United States in December 1851, and toured the country for seven months hoping to secure aid for his cause [Figure 13]. Kossuth was also featured on a cologne bottle which may have been intended to hold a toilet water dubbed Hungary water.

Others had the name of the glasshouse as part of a decorative molded inscription, an indication of how fiercely competitive the industry was at the time. Such flasks are of immense importance in documenting a place of manufacture, and they provide evidence that glasshouses from New Hampshire to Kentucky were involved in the business.

Although responsible for the artistry of these flasks, their designers and moldmakers, with few exceptions, remain largely anonymous. Larger factories, like the Bakewell firm in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, or the Boston and Sandwich Glass Works in Sandwich, Massachusetts, developed their own machine shops for molds. In 1828 Deming Jarves, of the Sandwich firm, for example, persuaded Hiram Dillaway to leave a South Boston moldmaker to work for the larger firm.26 But many could not afford their own mold shops, and they often obtained molds from urban centers. One notable exception is Philip Doflein, a moldmaker working in Philadelphia from 1842 to 1899, whose name appears molded on the bottom of the Kossuth bottle: “PH. Doflein / Nth. 5. TS.T84” “Mould Maker” [Figure 14].27

An especially American phenomenon, figured flasks were made in extraordinary numbers and hundreds of different patterns from about 1815 until the 1870s. By contrast, only three or four dozen patterns of similarly decorated flasks from England and Europe are known. The significant quantities in which they were produced is attested in an advertisement dating to 1825, for example, when Dyott claimed that he had 3,000 gross (or 432,000) flasks with his portrait alone.28 Dyott prided himself on the fact that his was an alcohol-free company, in spite of the fact that his fortune derived from consumers who did not share that predilection. The temperance movement was gaining strength throughout the nineteenth century, but as the number and variety of figured flasks suggests, America’s demand for liquor flasks continued unabated.

There is much more to learn with regard to assigning undocumented flasks to a particular glass house. Analysis of the inherent materials helps. A spectrographic study of the chemical compositions at the Winterthur Museum’s extensive collection of pictorial flasks, for example, determined that only four bottles had a significant lead content (30-40%), probably indicative of the fact that they were made in a specific glasshouse.29 This brief overview is just a start. It is hopeful that further studies will be forthcoming, and that this précis might spawn interest in transatlantic connections between American flasks and bottles produced through the third quarter of the nineteenth century. and those made across the Atlantic.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen

Figures

Notes

1. ↑ “Advertisement for Thomas Tisdale,” Connecticut Courant, June 30, 1788.

2. ↑ Arlene M Palmer, Glass in Early America: Selections from the Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum (Winterthur, Del.; New York: Winterthur Museum ; Distributed by Norton, 1993), 346.

3. ↑ Cited in Helen McKearin and Kenneth M Wilson, American Bottles & Flasks and Their Ancestry (New York: Crown Publishers, 1978), 380–81.

4. ↑ Female Spectator, 1750, cited in ibid., 378.

5. ↑ Their working dates are confirmed by Boston city directories. See Palmer, Glass in Early America, 347.

6. ↑ Richard Parker inventory, 1772-133, Philadelphia County Probate Records (microfilm, Winterthur Library), in Palmer, Glass in Early America, 348.

7. ↑ Ibid.

8. ↑ McKearin and Wilson, American Bottles & Flasks and Their Ancestry, 292.

9. ↑ It was estimated that during the early nineteenth century, American alcoholic consumption averaged about 15 gallons per person per annum. See Kenneth M. Wilson, American Glass, 1760-1930: The Toledo Museum of Art (New York; [Lanham, Md.]: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Toledo Museum of Art ; National Book Network [distributor], 1994), Vol. 1, 89.

10. ↑ Correspondence, 7 November 1820, John Pintard and Dorothy C. Barck, Letters from John Pintard to His Daughter, Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson, 1816-1833, Etc. [Edited, and with an Analytical Index, by Dorothy C. Barck. With Portraits.]. (4 vol. New York, 1940), Vol. 1, 343 in Peter M. Kenny et al., Duncan Phyfe: Master Cabinetmakers in New York (New York; New Haven [Conn.]: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Distributed by Yale University Press, 2011), 119.

11. ↑ Maryland Gazette or the Baltimore Advertiser, April 7, 1789, 3, quoted in ibid., 90.

12. ↑ Arlene Palmer, “Glass Production in Eighteenth-Century America: The Wistarburgh Enterprise,” Winterthur Portfolio 11 (January 1, 1976): 79.

13. ↑ Ibid., 85.

14. ↑ See Arlene Palmer, The Wistars and Their Glass 1739-1777 (Millville, N.J.: Wheaton Historical Association, Wheaton Village, 1989).

15. ↑ Tisdale advertisement, Connecticut Courant, June 21, 1790, quoted in McKearin and Wilson, American Bottles & Flasks and Their Ancestry, 28.

16. ↑ Palmer, Glass in Early America, 364.

17. ↑ Leslie Greene Bowman, “An Engraved Stiegel Pocket Bottle,” Glass Club Bulletin no. 147 (Fall 1985): 3–5.

18. ↑ Palmer, Glass in Early America, 361 (Cat. no. 351).

19. ↑ Ivor Noël Hume, Archaeological Excavations on the Site of John Frederick Amelung’s New Bremen Glass Manufactory, 1962-1963, 1963, 185.

20. ↑ The term “figured” was used by John Mather, a merchant and bottle maker from Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817, when he advertised “200 gross of figured Pocket Bottles, suitable for the southern markets.” Cited in Kenneth Wilson, American Glass, 1760-1930, 91. For an in-depth study of American figured flasks, see McKearin and Wilson, American Bottles & Flasks and Their Ancestry.

21. ↑ Apsley Pellatt, Curiosities of Glass Making: With Details of the Processes and Productions of Ancient and Modern Ornamental Glass-Manufacture. (London, 1849).

22. ↑ Wilson, American Glass, 1760-1930, 91.

23. ↑ Ibid., 91–92.

24. ↑ Like numbers were listed for other patterns as well. Aurora General Advertiser (Philadelphia), March 4, 1822, and United States Gazette and True American (Philadelphia), February 11, 1823, cited in Helen McKearin, Bottles, Flasks, and Dr. Dyott. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970), 35.

25. ↑ For a discussion of representations of Baltimore subjects on glass bottles, see Arlene Palmer Schwind, “Some Notes on Baltimore Bottles,” Glass Club Bulletin no. 130 (Summer 1980): 6–8.

26. ↑ George S McKearin and Helen McKearin, American Glass, (New York: Crown Publishers, 1948), 146, 335.

27. ↑ For more information on Doflein, see Miriam Mucha, “Solving the Mystery of Two Altered American Bottle Molds,” Journal of Glass Studies 26 (1984): 111–19.

28. ↑ Dyott advertisement, United States Gazette, March 3, 1825, cited in McKearin, Bottles, Flasks, and Dr. Dyott., 37.

29. ↑ See Janice H. Carlson, “Compositional Characteristics of Some American Blown Glasswares,” unpublished paper, November 1976, Winterthur Museum Library.